In 2021, over 200 people were killed as a result of the age-long sectarian violence between farmers and nomadic herders in Plateau State. In search of lasting solutions to the crisis, investigative journalist GABRIEL OGUNJOBI went to several agrarian villages in Plateau and Kaduna states. He returned with evidence of the complicity of the Nigerian Army in brazen ethnic cleansing, and uncovered how boundary loopholes are encouraging violence.

NIGHT OF TERROR

Hukke, Plateau – The day was shiny bright and it seemed quiet. This man, who pleaded anonymity, brought out his phone, placed it on a stool beside him at his hut in Miango central, and began to replay a recorded phone conversation between two men from the Irigwe and Fulani tribes. The recording lasted six minutes.

Miango is one of the two districts in Bassa, a local government populated by the Irigwe ethnic group. Irigwe’s chiefdom is spread across over 50 communities, towns and villages in Miango district and Kwall.

‘IS IT FAIR’?

“What your people did to us, is it fair?” Asked the Irigwe man, his shaking voice cracking very often as he spoke.

Over the phone, the Fulani man answered: “See, to God, we don’t see you people with any faults. Your people that live inside are the ones coming to deceive you. Our cows were grazing, but you people placed a flag, killed a boy and cut off his head.

The Fulani’s grouse was that the Irigwe farmers denied them access to freely graze on their farms. A teenage herder was killed on the farm in Hukke for going beyond the grazing area the Nigerian Army had given them, an incident the Irigwe native said his kinsmen should not be blamed for.

The killing of this young herder had consequences.

AUDIO: A Conversation Between Members of Two Warring Plateau Communities

THREE VIGILANTES SHOT DEAD IN AN AMBUSH

Before this call, there had been an attack in Hukke. On October 3, three people, all local security guards, were shot dead while trying to repel attackers from invading the community.

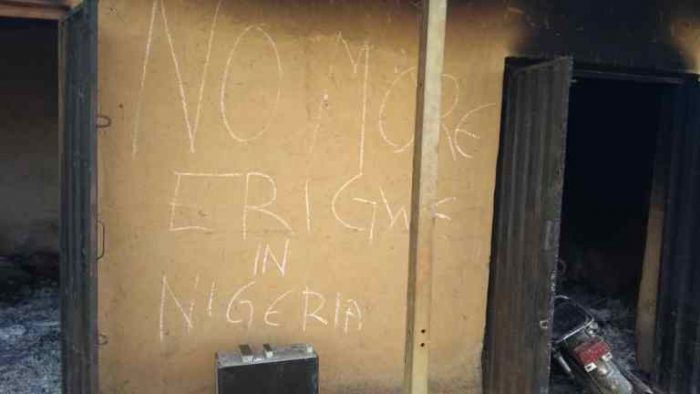

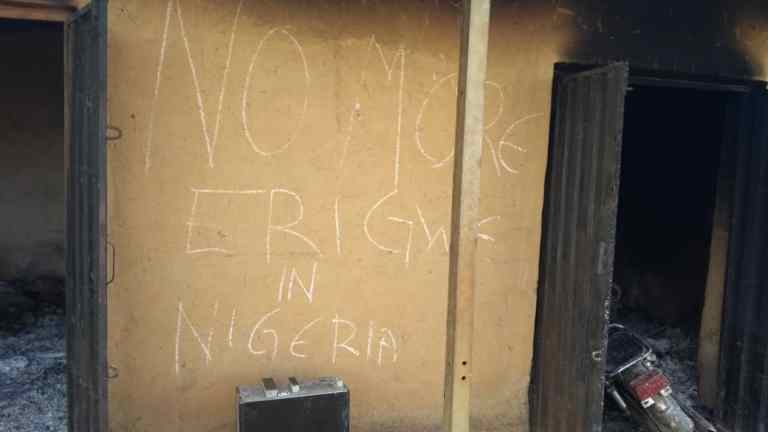

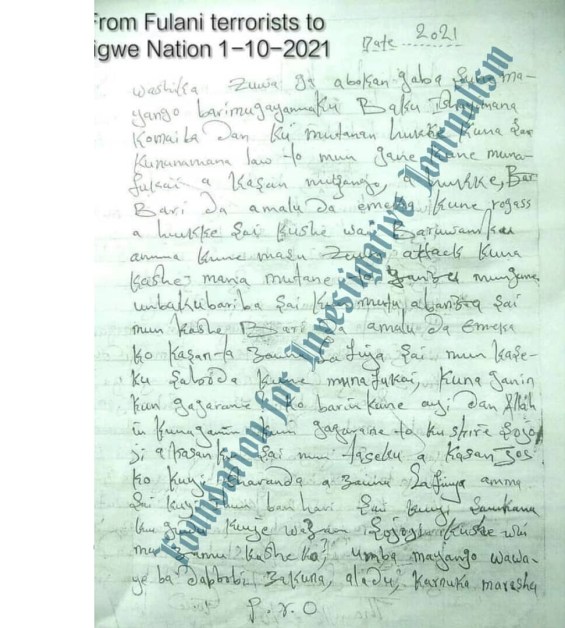

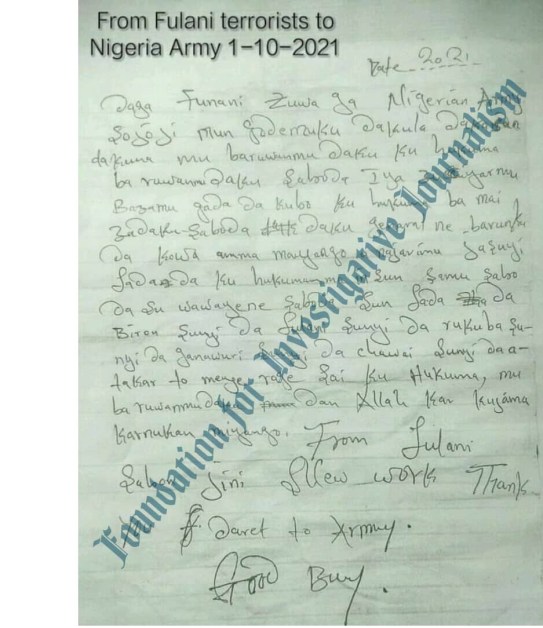

Just days earlier, “Fulani terrorists” dropped a two-part letter on the hill in Hukke where an army commandant erected a military flag to set grazing limits. While the Nigerian government has not yet declared any Fulani-affiliated group a terrorist sect, they called themselves terrorists in the letter.

In a village next to Hukke, called Ancha, another commandant in the Nigerian Army erected a red military flag. These flags were a part of the army’s steps to reduce and eventually stop the conflict within the Bassa Local Government Area of Plateau.

“We’re leaving you because of Allah, but if you think you’re unbeatable then prepare your army. We’ll meet in the land of Jos or you surrender and we stay peaceful,” a part of the letter addressing the Irigwe people read.

In the second part, a subtle warning to the Nigerian Army, these faceless letter writer(s) implored the Nigerian securities not to defend the Irigwe people whom they likened to dogs.

As translated from Fulani language to English, the part of the letter addressed to the Army read:

“We appreciate your efforts in safeguarding the nation; we don’t have problems with you because you’re an instituted authority. We can’t try you because you’re an instituted authority with the general and you don’t swindle in civilian affairs. Because they’re fools, Miango people can fight with the authorities as they’ve fought with Berom, Fulani, Rukuba, Ganawuri, Chawei and Atakar. So who’s left to fight if not the authorities, we don’t have anything against you. For Allah’s sake, don’t deal with Miango dogs”.

– Letter by the ‘Fulani terrorists’ to the Nigerian Army

Major Ishaku Takwa, the military information officer for Operation Safe Haven, a special task force (STF) in Plateau State, told FIJ he was not aware of such a letter. But the villagers insisted the army had held a meeting with the farmers and herders before the eventual attack.

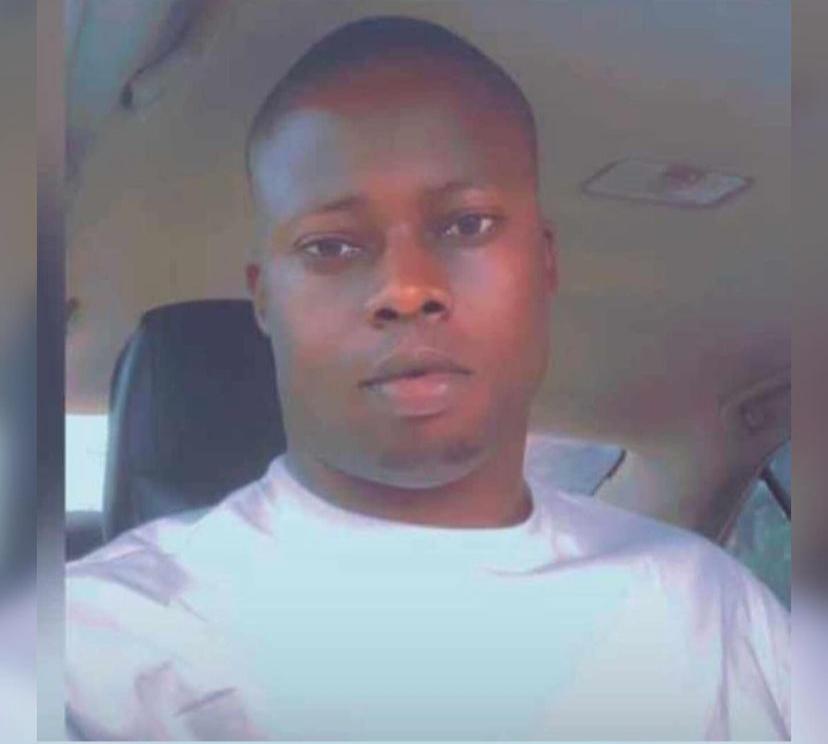

At midnight on October 3, Gbere Bosco, the arrowhead of Hukke vigilantes, heard a gunshot from the bush.

A young man was shot in the thigh. This was a new tactic employed by the raiders. To outsmart the military and local vigilantes, people are lured out of their homes into an ambush. When the locals retreat, their homes are rounded up.

That evening, Bosco rallied his men around and attempted to follow the trail of the gunshot. Soldiers deployed to the town joined in the search. None of them saw the attackers.

“As we were returning to the village, we came under fire,” said Bosco. “Some villagers rushed the injured boy to the hospital. Our plan was to get back home and take a position against any impending attack while the soldiers also stayed in the bush, but we didn’t know the Fulani had laid ambush for us.”

Bosco received a bullet in his chest. Nightfall prevented the shooters from aiming at him the second time, but his three other colleagues were not so lucky; they tried repelling the enemies but lost their lives in the course.

“The bullet went from my chest to my right leg and it is lodged there as I speak,” he told FIJ. A doctor has told Bosco that it is inadvisable to remove the bullet. At this rate, it will take a lot longer for him to fully recuperate. If the surgery is untimely or incorrectly done, the flow of blood might not be suppressed. Bosco is able to walk but feels pain when he walks for a long time.

After Sending Warning Letter to Army, ‘Fulani Terrorists’ Invade Plateau Community

- THE BEREAVED [1]: ‘A MAN WHOSE HUMANITY KILLED HIM’

As Sarah Barrie mourned the death of Ivy, her husband and one of Bosco’s colleagues shot dead in the October 3 attack, She had new issues to deal with.

Until his death, Ivy usually rode his two youngest children, aged 5 and 7, on a bike to their school in Miango town. He would then make a detour to the farm from there. But now, if the children are not able to trek to school, five kilometers from home, no one can help them.

Asked what she missed the most about her husband, Sarah minced no words: “His compassion for humanity”.

“It was the same heart of humanity that made him join the vigilante group before he was killed on the job,” she said. “My husband didn’t drink or fornicate. That night, he went to see what was happening, but was shot dead.”

Sarah’s first and second sons, Bulus, 22, and Joshua, 19, have completed secondary school education but the future looks bleak. The deceased father’s responsibilities are on their shoulders now. They have to care for their mother, younger ones and attend to the farm left behind.

Joshua, 19, now expresses doubts about ever returning to his shoe-making apprenticeship in Jos.

‘ROUTES OF DEATH WHERE SOLDIERS DO NOT DARE’

Danladi Agra became worried that he could neither earn a good living from farming nor live without fear of being attacked by certain Fulani looters who often set an ambush on their farms.

Many farmers have been killed and farmlands burnt and deserted. He lost his teenage nephew in 2018 in an ambush attack.

“They entered our irrigation farms and destroyed it. That was around 2017,” Agra began as he detailed how farming had gone from bad to worse for him, ultimately sending his five children out of school. “We just noticed that they were laying ambush along the road between the outskirts of the Te’egbe and Chawai in Kaduna. They killed our women who went to fetch firewood.”

Asked if he knew the attackers were Fulani, he said, “They began with grazing on our farms, but we resisted them from destroying the crops.

“They left and, after some time, phoned our community leader with a threat to attack because we stopped them on the farms.”

To preserve his own life, Agra abandoned his farm in the far-flung region of Te’egbe. The cattle will now feed fat on the land he dares not step on.

About 70 percent of Nigeria’s labour force is employed in the agricultural sector, with most small-holder farmers like Agra cultivating yams and vegetable crops. The competition for land with herders is fast running the nation into food insecurity across the middle-belt, such as Benue, Plateau, and Kaduna in the north.

Climate change keeps pushing these farmers to different locations where water is available and crops grow within the shortest time possible. Now, the limited arable land to graze or cultivate is no longer there.

Exactly 10 days after having this conversation with Agra, the marauders revisited Te’egbe and killed 10 people. Some were charred in their sleep and others ran into flying bullets.

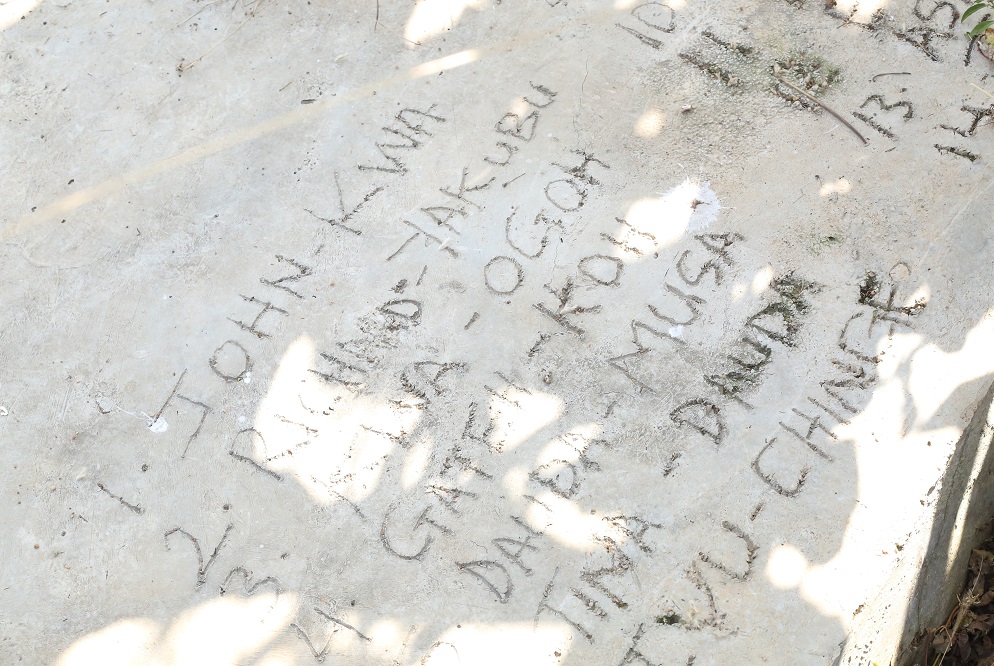

Barns of food items were wrecked. Huts were set ablaze. The army’s lodge was not spared either. With hundreds of villagers now displaced, no one wished an end to this siege more than the bereaved John Gara, whose father, mother, nephews (six of them) are part the 10 that were gruesomely murdered.

“Please help us do something about it,” he told FIJ tearfully. “Our place is close to Kaduna and these people often come on motorbikes. That night, they parked the bikes at a distance and marched in on foot.”

Gara insisted that there were no state actors manning the area the assailants came from, saying, “Even the soldiers could not wait while the attack was going on”. His stance corroborated claims that the unmanned boundaries between Kaduna and Plateau are aiding illegal movements and proliferation of firearms which exacerbate the conflict in the region.

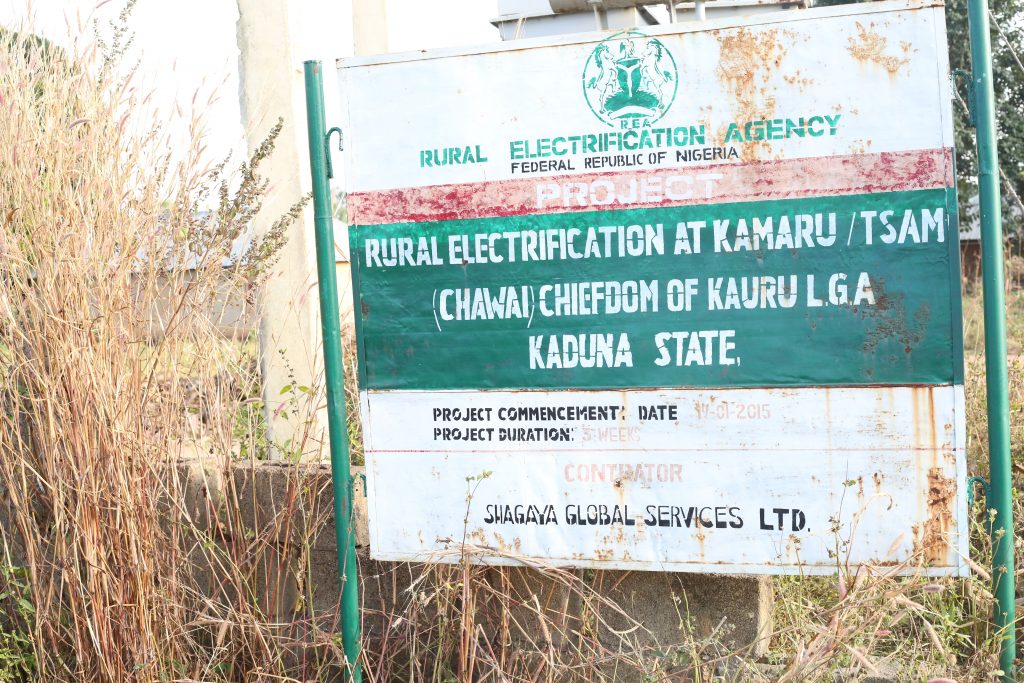

Like Te’egbe, Kwall is also another community along the boundary of Kaduna in the east of Plateau. Te’egbe village in Miango is four kilometres to Baduru in Kaduna. Kishesha, on the other hand, is the closest route to infiltrate Kwall from Kamaru, a forest in Kaduna. Kwall has lost up to five villagers in 2021 alone.

To fact-check the assertion of a porous boundary, this reporter embarked on a tumultuous motorcycle trip from Kwall to Kaduna.

A few kilometres away, there was an expanse of farmland Simon Lalong, the state governor, visited on November 9, on behalf of President Muhammadu Buhari, to commission a first-of-its-kind rainfall wheat farm. The event is Lalong’s only visit to Kwall and Miango since the crisis returned in July/August.

For this reporter, the fear of travelling across this route was palpable because incoming riders could be anyone, such as the illegal tin miners or some potential attackers strategising inside Kamaru Forest in Kaduna.

‘We’ve Been Fighting a War’ — Man Narrates Experience With ‘Fulani’ Herdsmen in Plateau

Aside from the extra 15 to 20 minutes the motorcyclist spent to fix his deflated tyre, journeying into Kamaru town takes two full hours. There was no military checkpoint and no sight of any security personnel.

Inside Southern Kaduna, the intensity of farmer-herder crisis was just like what was happening in Plateau. At the height of the face-off sometimes in 2017, Ungwan Rimi lost its king.

Kauru Local Government Area in the Southern Kaduna axis shares a boundary with Plateau State to the southeast. It is dominated by a number of ethnic groups, including Abin, Atsam and Irigwe.

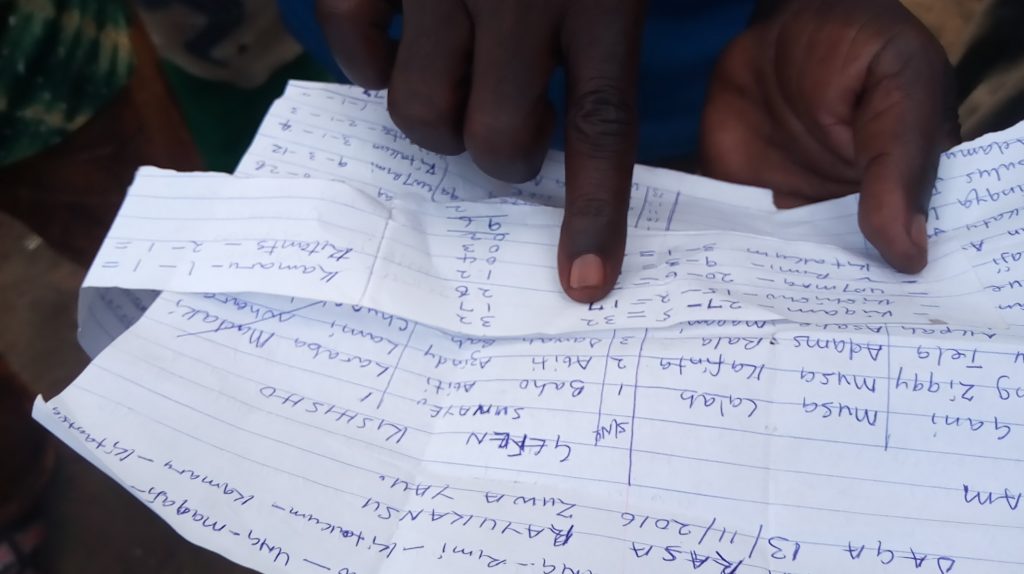

“The way they are disturbing you there, they are killing our people here too,” Adamu Ibrahim Alkali, a village head in Kauru told this reporter, dipping his hand into the pocket to display a list of the murdered people.

From 2016 to date, he said, 96 people (all Irigwe natives) were killed in a series of attacks executed by the Fulani. The casualties were spread across Kamaru, Kishosho, Kitam, Kigam, Ungwan Magaji and Ungwan Rimi.

“We are all Irigwe. We are one with you but we don’t have the manpower to help you people there,” Alkali said. “These people are cattle rearers and they are Fulani people who don’t settle here. They always come from Chawei to destroy our farms and go free.”

- THE BEREAVED [2]: CHILD OF WAR

Until Ruth Sunday, a seven-month-old baby of Maiyanga, becomes an adult, she may not be told how she survived infancy. Otherwise, she may have bouts of trauma to deal with.

When the International Christian Concern learned about Ruth’s experience, she was named the youngest persecutor. Hers is a story of ‘a plea to live’. Hannatu Joshua Yakubu, her mother, knew she would die. Her prayer to the killers was to spare her baby.

“They wickedly did,” said Mary Bernard, the elder sister of Hannatu, now Ruth’s caregiver. “They said even if they let her live she would die of cold on the rock.”

Three-month-old Ruth survived. The attackers shot two of her cousins and their mother dead, said Mary. One was five months old and the other was three years old.

Over 20 villagers, including Ruth’s mother and grandmother, were trying to escape the raiders that invaded their homes on August 2 before getting stuck by the bed of an overflowing river.

The attackers caught up with them there and shot some of them dead while some others escaped. Ruth’s survival without scar was divine; her grandmother’s experience was near-death: she was shot in the thigh before the attackers moved on to another village.

A few hours later, the cry of Baby Ruth beckoned to the surviving villagers who were picking up carcasses. Both survivors were then urgently transported to hospital.

Ruth now lives at the mountaintop on the Rukuba road in Jos, a place where the dew covers homes in early November and the cold is at 11°C.

People live in the chilly houses on rocks because the valleys are congested in the cosmopolitan Jos city.

Ruth’s caregiver hopes she is able to “turn the baby into a child of testimony”.

“It will also be my wish if any donor is kind enough to sponsor her education,” she told FIJ. “Ruth’s greatness will make the death of her mother worthwhile.”

ARMY’S ROLE: TO CONNIVE OR TO PROTECT?

Zahwra, Plateau – Under the same circumstance Ruth’s mother died, many other villagers in Miango and Kwall districts were slain. Others were displaced.

It was a bloody raid that lasted nearly a week between late July 28 and the first week in August, as if the attackers meant to dare the soldiers to act.

Farmlands on the Plateau turned into graveyards overnight. The number of dwellers in Jos, the capital city, exploded due to the displacement of farmers in these ravaged villages. For instance, the forceful eviction of Bitrus Gana and her pregnant wife (now a nursing mother), Kanygang, from their home in Jebbu, meant the suspension of ‘Jebbu Miango Reads’, a volunteering evening class to bridge school enrollment gap among the farmers’ children.

VIDEO: House razed in Jebbu-Miango village during the July/August attack:

Like many locals in Jos, Heli Musa, a driver with Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA), began to host 31 people in his small apartment while earning just a meager income. Many schools and churches became makeshift homes for the widows, widowers, and their children.

By mid-September, Dachung Bagos, representing Jos East/Jos South Federal Constituency, professed before the House of Representatives that the killings were no longer farmer-herder clashes but genocides.

Although the stem of violence in the middle belt state can be traced back to a former military head of state, Ibrahim Babangida’s policy to create Jos North LGA in 1991, the patterns of killings became efforts to seize lands and wipe out indigenous ethnic groups.

The Plateau indigenes, predominantly Christians, protested against the creation of Jos North, seeing it as a move to impose Hausa-Fulani settlers, who were largely Muslims, on them. The subsequent resistance led to killings from 1994 to the late 2000s.

With the political uproar already set in motion, the tussle for dominance moved from politics to ethno-religious violence, wiping away an entire Irigwe from 2016 to date.

In the midst of reprisal attacks between farmers and Fulani herders over space for land and water, many have a reason to believe that the clash has been hijacked by criminal gangs, who hire out-of-school almajiris from various states of the country and on a larger scale from the countries bordering Nigeria’s northwest.

Those who witnessed these attacks are more heartbroken because “the soldiers watched and claimed they were not given orders to shoot”.

“I forgive these Fulani militias but I find it hard to forgive the government because they neglected us in our times of need,” a villager in Tafi-Gana, who pleaded anonymity, told FIJ.

“It was even interesting how the attacks started. They first started by laying ambush for three or four farmers, then moved on to the destruction of farms. On the night of August 2, about 200 of them engulfed Miango. They were so coordinated that while some were shooting, others were looting the houses.

“If you manage to escape the fire, your house cannot escape looting. In fact, some groups will load properties in their trucks and some others will set the houses on fire.”

– A survivor of July/August attack from Tafi-gana

Survivors noted that the attacks were led by their old Fulani herder-neighbors who lived in Rafin-Bauna and Dutsen Kura but suddenly began to evacuate Bassa LGA some years ago, only to return in a brute force. More so, these locals challenged the Nigerian government to investigate the Nigerian Army in order to fish out saboteurs providing intelligence to the enemies.

Not only do the stories tend to validate claims of the government’s complicity, the pieces of evidence available corroborate the same. One of such facts is the significantly close proximity of military checkpoints and barracks to the sites of major attacks.

Geographical coordinates from Google Earth’s satellite imagery showed that DTV village shares a fence with the Third Armoured Division of the Nigerian Army where President Muhammadu Buhari served as the General Officer Commanding (GOC) between 1981 and 1983. Aside from the fence, there is a military checkpoint at the entrance of the village. Beside DTV is Nche-Tahu, which is just about five minutes drive away from the same 3rd Armoured Division.

Zahwra and Jebbu Miango, the most ravaged villages, are three to four kilometres each from the military barracks. FIJ observed that Operation Safe Haven also has a lodge in the middle of Zahwra and there is also a military checkpoint at the expressway. At Jebbu-Miango, there is a police station and an Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) controlled by the STF military personnel.

Only Miango central, which has a police station beside Enos Hospital and an APC operated by the military, has not suffered any attack within the Irigwe chiefdom of Bassa.

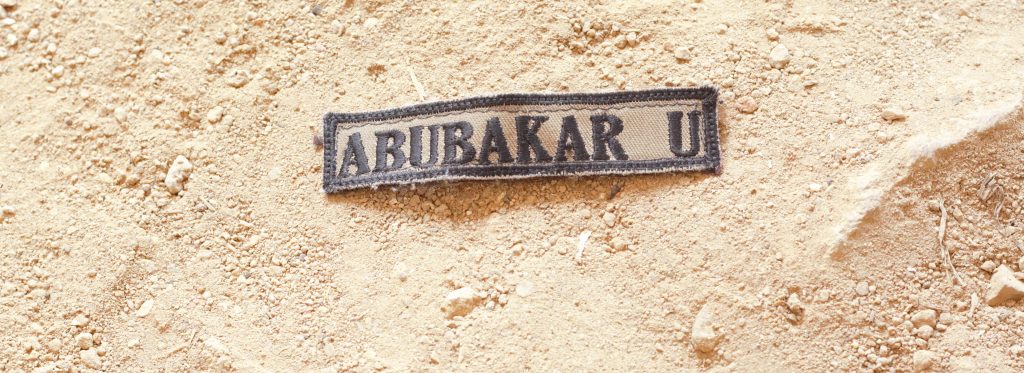

Also, this reporter discovered a military tag in the rumble of mud within Zahwra village. The name on the tag read: ‘Abubakar U’.

A source in the Nigerian Army told FIJ it was difficult to trace the actual person bearing the name without raising suspicion, especially as soldiers are being transferred out of Miango within three months of deployment.

“By the way, the bandits and Boko Haram also wear camouflage,” he added. “They are the ones who make these uniforms now expensive for the army because the fake materials are rampant in the market.”

On the allegation of inability to shoot during an attack, our source further said, “There’s no smoke without a fire. Jos crisis is political. The rule of engagement is never to shoot under such circumstances. Soldiers will never strike back unless one of them is hit by a bullet”.

If these words are anything to go by, military personnel are rarely shot at during the siege. So, their resistance may not be provoked, going by the soldier’s confession.

In fact, in the October letter which FIJ exclusively obtained, the ‘Fulani terrorists subtly asked the army not to meddle in their affairs with Irigwe, as the state actors were not their targets.

READ ALSO: How Police Refused to Shoot as Fulani Militias Wiped Plateau Community

In 2017, Bulus Dali, a 70-year-old farmer, recounted the most devastating example of the army’s complicity. This time, the military brought a potential disaster on the villagers of Nkiedonwhro. They ushered the women and children to take shelter in a school, which was their makeshift home. But after the civilians had done so, eyewitnesses said, the soldiers signalled the assailants with a shot in the air. A short while later, the soldiers were nowhere to be found. The assailants, from whom these civilians hid on the advice of the army, went directly to the classroom and fired into the cowering villagers, killing 30.

Dila said the disaster had made villagers lose confidence in the army, with many vowing never to return home.

“As for me, I’m not going to run anywhere; I was born here and this farm is my legacy,” he said, as if to dispel the fear of a revisited attack. “Even though all my children have relocated to Jos city since the 2017 incident. I’m not afraid of death again.”

- THE BEREAVED [3]: ‘A HORRIBLE GOVERNMENT ATTACK’

Behind Rejoice Ishaya’s house is the military’s bungalow and in front of hers’ is the checkpoint, one of many lined up between Zanwra and Rukuba road. Yet Ishaya feels unsafe, with little confidence in the army.

She lost a 30-year-old brother, Cannan, two cousins; Joshua and Ezekiel in the July/August attack.

“It was a very horrible and terrible government attack,” she said, recounting the incident. “The way the Nigerian Army attended to the situation, it seemed they knew things about it, and that the attackers were sent.”

“In my own opinion, these Fulani we see around here are not as much as the attacks they did those days. From their way of operation, there is the government’s hand in it to hire mercenaries for them.”

– Rejoice Ishaya

“Sometimes they come as many as 500. That is why I said it seems the government is helping them hire more people from other countries or maybe our Muslims brothers are helping them.”

What Rejoice held back from saying, she eventually let out.

“The lower-ranked officers are not always the problem, but the superiors that give them permission to do something. They are the ones that call them,” Rejoice noted.

“I can remember very well when this attack was happening. The army commandant of this place tried to do something but he had a call from their headquarters. That is why it seems to me like the government is helping them (attackers). It seems like they have the contacts of the government.

“When the attack started, the soldiers were here,” she said, pointing in the direction of the army’s lodge at Zahwra. “But, they just asked them to go to the checkpoint and nobody was here again. Even their windows got hit just like ours.”

At the moment Ishaya was talking, some Fulani herders were grazing their cattle on the pastures in Zahwra.

MIANGO’S REST HOME IS NOT FAR-FETCHED IF…

The year was 1893. Three young men, Walter Gowans, Thomas Kent and Roland Bingham braved the odds of malaria and harsh climate to settle in Nigeria for mission work. Within the first year, Gowans and Kent died of grave illness as they could not survive Africa’s temperature. Bingham too was invalided when he nearly died.

For the sake of the gospel, daring Bingham returned and by 1910 Sudan Interior Mission (SIM) had a firm foothold in Nigeria. In his lofty dream, he thought missionaries would need a suitable place in the highlands to build a sanitarium which meant ‘a health resort’.

Miango in Plateau would later become that chosen site. Over 100 years later, the edifice named ‘Miango Rest Home’, which many once laughed off and professed would fall at the whistle of a storm, is still elegant without any record of attack up till date in the midst of the chaos. The ambience at Miango’s rest home lavished the splendor of its bright colours from the gate, and the hummingbirds inside it made a melody to the hearing, not like the drums of war beating every other place miles away. The culture of communal dining in MRH is retained for all tourists regardless of class differences. And the stones that set the structures over a century ago are yet to be changed.

If Plateau preserves its epithet as‘ home of peace and tourism’, MRH puts the icing on the cake. However, a gift from a widow, Evelyn Webb-Peploe, engineered Bingham’s dream to this adorable reality. Evelyn had married Robert Webb-Peploe at the time he was diagnosed with pulmonary heart disease. The two devoted Christians lived the most parts of their service years for humanity in Canada. In fact, before Robert was laid to rest in 1904, the couple hosted a congregation of cattle herders, a sort of life that has become a problem in this dispensation.

So, MRH typifies a powerful love account and a sweet-smelling incense: the story of emigrants who lived peaceful and prosperous lives in a strange land and also of a large-hearted widow willing to share from her little.

For the Irigwe people to live in harmony with the Fulani herders, Alkali, the Kaduna village chief’s piece of advice is that “Any village head who agrees that Fulani can stay should allow them to rear only in that area. Any village where they are not allowed, they should also stay away from there”.

But the Fulani want more, said Chief Daniel Chega, the Miango district head. “They prefer to come from outside our territory, destroy our farms and go back,” he told FIJ.

“Our stand has always been that if the Fulani herders want to come back, they should register with the village authorities so that we can know everything about them in case of trespass.”

As a district head, Chega is at the centre of peace talks with Fulani to end the cattle crisis but he is not immune to death threats. On his way from their regular meeting with the Fulani neighbours at the local government secretariat, sometimes in September, he was almost hit by a bullet targeted at his car.

Peace efforts have failed many times in the past. Since the 1990s, at least 14 commissions of inquiry and committees have been established over Plateau killings, but most of their recommendations were criticized over biases against Fulani.

At the national level in 2019, the federal government inaugurated a 10-year National Livestock Transformation Plan as an alternative to open grazing of cattle to prevent farmer-herder crisis.

The NLTP would initially support the development of pilot ranches in each of seven pilot states of Adamawa, Benue, Kaduna, Nasarawa, Plateau, Taraba and Zamfara. Up to date, the implementation of NTLP is grounded.

A report by the International Crisis Group (ICG), titled ‘Ending Nigeria’s herder/farmer crisis: The Livestock Reform Plan’ attributes the failure to “inadequate political leadership, delays, funding uncertainties, lack of expertise and COVID-19,” adding that “If this initiative fails, there could be more rural violence. Abuja should work with donors to raise both money and awareness of the scheme’s benefits.”

- ‘ALL SIDES ARE CASUALTIES’

Back in Bassa, all sides, including Berom, Rukuba, Irigwe and Fulani, are casualties. The blow is harder in some parts nonetheless.

Abdullahi Ardo, the secretary of Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN) in Plateau State, explained that the majority of the Fulani people “are radio listeners and hardly on social media. So they don’t have a chance to clear themselves of many allegations”.

“There are lots of criminalities going on but people often blame it on the Fulani because we have no voice. So, we decided to keep shut and watch since there is no justice and people are not ready to hear the truth. The Fulani are also seriously affected.”

– Abdullahi Ardo, MACBAN secretary

Indeed, reports on Fulani casualties are scanty. In September 2018, MACBAN chairman announced that a baby herder was killed.

Abdullahi Abubakar’s son, Mustapha, was also slaughtered while he was tending to livestock in July last year. The suspected killer, an Irigwe farmer, is currently in prison over the incident, says Al Jazeera.

But the same way this news is scarce in the media, Miango community leaders query, “Where are the corpses?”

Gastor Barrie, who runs a nongovernmental organization offering humanitarian services to displaced persons in Plateau, agrees with the line of thought, describing the killings in Bassa as tinted with an ethnic agenda.

“These people destroy farmlands to allow them to graze, but they also chant Allahu Akbar when they attack,” he affirmed.

“They are bold to say they will take Irigwe land for Islam. There is ethnic cleansing and I can sense connivance with some of the military personnel because these attackers appear well-trained.”

While he was still speaking, Barrie hovered his index finger on a mini laptop placed on a couch in his sitting room.

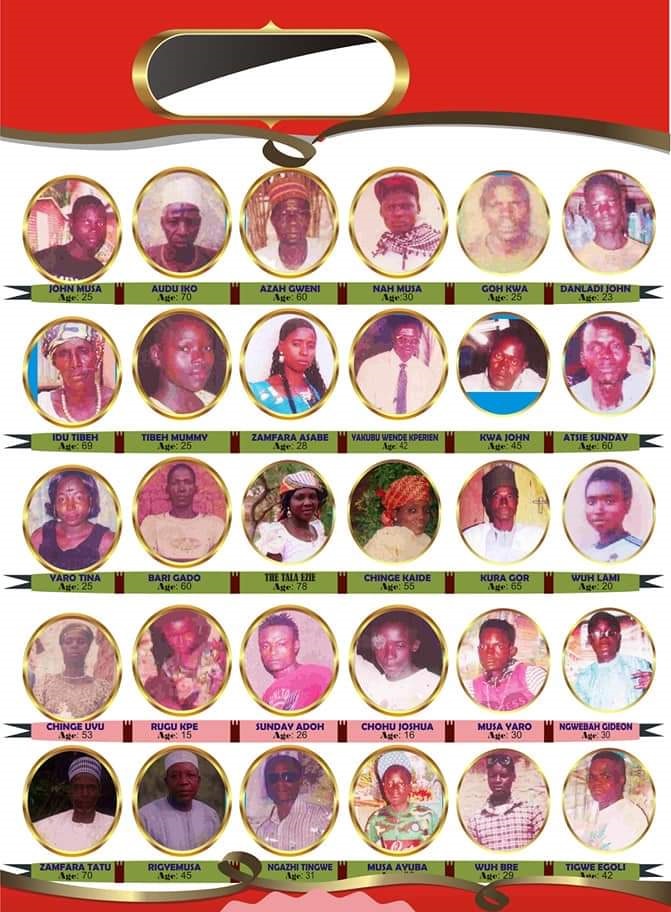

One after the other, he began to quote data on the losses and attacks. Most of them had picture evidence as well. Over 200 people have been killed in brutal attacks in 2021.

LIST OF SLAIN PEOPLE IN BASSA LGA IN 2021

| S/N | SLAIN PEOPLE IN BASSA LGA | AGE | PERIOD |

| 1 | Hannatu Joshua Yakubu | 20 | JULY/AUGUST ATTACK |

| 2 | Cannan Hassan | 20+ | JULY/AUGUST ATTACK |

| 3 | Joshua Sunday | 20+ | JULY/AUGUST ATTACK |

| 4 | Ezekiel Ishaya | 20+ | JULY/AUGUST ATTACK |

| 5 | Reuben Sunday | 30+ | OCTOBER ATTACK |

| 6 | Abednego Amos | 8 | OCTOBER ATTACK |

| 7 | David Amos | 30+ | OCTOBER ATTACK |

| 8 | Ivy Barrie | 42 | OCTOBER ATTACK |

| 9 | Isaiah Gado | 45 | OCTOBER ATTACK |

| 10 | Weyi Chohu | 40 | OCTOBER ATTACK |

| 11 | Daniel James | 32 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 12 | Zakwe Deba | 35 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 13 | Gara Ku | 80 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 14 | Wiye Gara | 67 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 15 | Tala Gara | 68 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 16 | Rikwe BalaYoh | 65 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 17 | Tabitha Danlami | 8 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 18 | Sibi Danlami | 4 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 19 | Friday Musa 35yrs | 35 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 20 | Daniel Mandi | 45 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 21 | Mweri Chogo | 86 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

| 22 | Ayo Balai | 6 | NOVEMBER ATTACK |

The MACBAN spokesman said he could not attribute this year’s killings to a particular incident, but described the pocket of attacks as reprisals.

He asked that community policing be established, integrating the Fulani and farmers in the structures.

Ardo’s idea is similar to a 2010 home-grown ‘Operation Rainbow’, a mix of security deployment with a civilian component, formed by former governor Jonah Jang. The security outfit was, however, retired after the serving Governor Lalong came to power in 2015.

ARMY SPOKESMAN’S CONTROVERSIAL COMMENTS

Despite the widespread allegations of complicity against the Nigerian Army in the killings in Plateau, the security outfit came to enmesh itself in more controversies.

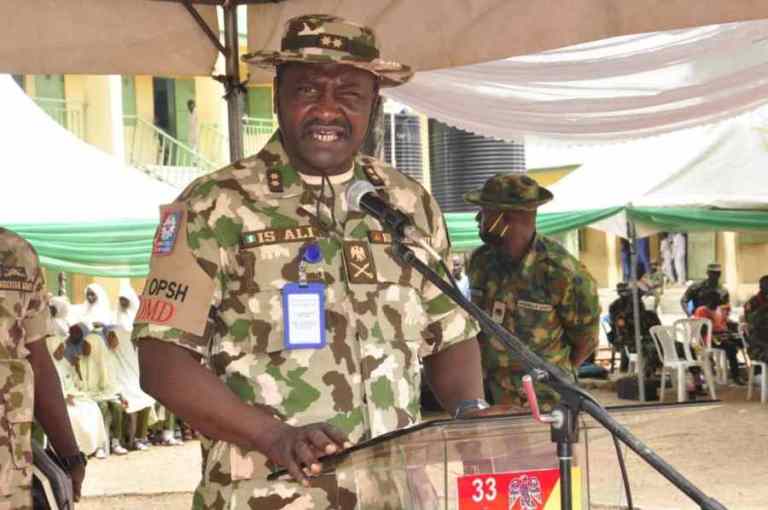

The multiple times FIJ spoke with Major Ishaku Takwa, the Military Information Officer for Operation Safe Haven of the Nigerian Army Command in Plateau after attacks, the spokesman showed no empathy but biases and denials.

AUDIO: FIJ’s interview with the Nigerian Army

“What is happening there is an act of criminality and the Nigerian Army is doing its best to stop it,” Takwa had said, after the most recent attack in Te’egbe where people died. “If you must know, these attackers are coming from Kaduna and the areas are mostly farms. Are we then going to have soldiers stationed inside the farms?”

Denying the receipt of the warning letter preceding an attack at Hukke in October, Takwa said, “Let them send you a copy and then you send it to me. You mean they sent a letter to the Nigerian Army that there would be an attack? These people are terrible,” he said.

“Let’s be truthful to ourselves in this country. I don’t know why people always like to indict the Nigerian Army. This is a very blatant lie. I remember that there are about eight to nine sections of troops in that Hukke area.

“So, when did they send the letter and we didn’t get it and they have our contacts? We distributed our contact helplines and so why didn’t they call the contact numbers?”

Takwa warned the community residents against plotting reprisals, saying, “Please, ask these people, anytime they are killed or injured, they run to the media, but they will not rush to the media when they attack the Fulani or other tribes in that area.

“We have told them that they must agree to stay together. We cannot follow them to the farm. They should stop attacking and counter-attacking.”

Produced in partnership with the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) with support from Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO)

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.