In August 2022, the Borno State Government shut its doors to formal IDP camps across the state, bringing an end to what has been eight years of housing the displaced while combating terror. One of the worst hit regions in 2014 was Bama, and some of its displaced indigenes cannot go back, writes DANIEL OJUKWU.

Hadiza Abubakar is a single mother of three, wife of an estranged husband, and an internally displaced person (IDP) in Dalori, Konduga Local Government Area (LGA) of Borno State.

Now residing in a makeshift shed directly opposite the camp that housed her family for seven years, she spends her days scavenging for food, farming or offering up her services for menial jobs to feed her children.

“They sometimes eat once a day,” she told FIJ of her children, while speaking her native Hausa. “When they don’t get anything to eat, they understand and go hungry until there is food to eat again.”

Until three months ago, Abubakar’s needs were being taken care of by the state government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other concerned parties, but since the closure of the formal IDP camps in August life has been difficult.

Prior to her relocation, she used to live in the Dalori II camp for displaced persons. She now lives in an informal camp across the road, with no fence or structure, and no access to water.

Her ordeal began on September 11, 2014 when Boko Haram terrorist sect invaded her town, beheaded men, raped women, and forced residents into hiding.

At the time, she was married to Umaru Salisu, a 40-year-old indigene of the state, and they both lived in Bama, the second largest Local Government Area (LGA) in Borno, with their single child.

“Boko Haram came that day and started killing people,” she recalled. “They took over the community, and we began living with them there.”

To survive the onslaught on men, she said Salisu joined the sect a year after, and she never heard from him again.

“I don’t know if he is dead or alive,” she told FIJ.

When he made this decision, they had birthed a second child. With two children and no husband to fend for them, she picked herself up and journeyed over 61 kilometres to Dalori camp for IDPs, where she would become known as an undocumented widow, meet another man, have a third child, and then leave with nothing after seven years.

‘SEMA PROMISED US N100,000 BUT GAVE N50,000… SOME EVEN GOT NOTHING‘

When more than 20,000 displaced persons were to vacate the Dalori camps between July and August, the State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA) promised to give N100,000 and some food items to each male head of a family, and N50,000 to widows, the dwellers here told FIJ.

In the camp, Abubakar was identified as a widow as she had no husband or male figure with her. But when she was to access relief materials and cash, the camp officials told her she was not registered for any benefits.

“I left the camp with nothing,” she lamented. “I just took my children and left to this place where we now stay. Everybody got some money, food items and mats, but they said I was not registered.”

Her plight was unique. Earlier, men in this same settlement had told FIJ that SEMA promised widows N50,000 each, but gave them N25,000 instead, and pointed us to Abubakar to ask. Until that point, no one in the settlement knew she was left out, they all assumed she had benefited from SEMA’s ‘half-a-loaf’ disbursement, until she told us otherwise.

On the afternoon of October 21 when FIJ spoke with her, she was on a mat, drinking a mix of garri (processed cassava) and groundnuts, while recovering from what she believed to be malaria. The only healthcare centre around was closed, and she had no means of getting professional help.

Her three children were playing in one of the rooms, while she was sat outside, struggling to speak, and unwilling to look our reporter in the eye as she laboured to narrate her past.

Her past was not unique to her. A 32-year-old man who identified himself simply as Murimaina told FIJ he had been in the formal camp for close to a decade, until he was made to relocate.

With a wife and five children to cater for, he farms daily to fulfil his responsibilities as a father, but told FIJ they never eat three square meals. “If I eat once a day, I will be fine,” he told FIJ. “If there is food, the children eat; if there is none, they don’t.”

He opened a room behind him, and exposed where harvested maize was stored in the settlement.

“We get water from our rich neighbours,” he told FIJ while gesturing towards houses behind where they lived.

“Sometimes they allow us fetch, other times we may not be so lucky. We also do not have access to toilets. We use one pit close to the entrance there, or we go to a nearby river.”

When FIJ checked this pit toilet, our reporter found it in poor condition and directly facing the road, with little covering.

Murimaina told FIJ that as the male head of his family, SEMA, in August, gave him N50,000, one bag of maize, one bag of rice and a carton of pasta before the camp’s closure.

He said, “Government promised us N100,000 and food items, but they only gave us N50,000, and gave N25,000, a mattress and mat to women.”

Asked about widows, his neighbours reacted and answered on his behalf.

Wani Bukar, another dweller here, said the government told the widows to expect N25,000 but it never came.

“The governor sent delegates to ask us to leave the camp, but that was during rainy season; it rained every day and we were unable to farm, but they closed the camp.”

Abubakar was one of such ‘widows’. She told FIJ that while she was in the camp, she had no man with her. The man who eventually took interest in her ended up impregnating her and abandoning her to what became her third child.

Bukar further said these ‘delegates’ asked them to visit their local governments for the fulfilment of the promises, but such visits yielded no result.

On why he had not returned to his ancestral home of Bama, Bukar said his house was razed by terrorists. “My house was burnt to the ground; the site where it stood is now empty. Even my farm is gone,” he said.

“Presently, the army is in the location I used to call my home.”

30 CHECKPOINTS, HEAVY MILITARISATION EN ROUTE TO BAMA

Since the Army recaptured Bama in March 2015, it has maintained heavy presence in the area to forestall potential attacks by the insurgents.

At the time, Boko Haram was using Gwoza, the state’s largest LGA, as its headquarters.

From the park in Maiduguri to Bama’s entrance, there were 30 checkpoints: 27 manned by soldiers, two by policemen, and one by road safety officials.

At most of the checkpoints, drivers squeezed a N50 note into the hands of a soldier before they were allowed to continue. Some handed N100 or N200 notes to the soldiers, but got change in return.

This practice was very common, and the drivers did not wait to be told before they performed the ritual. They would smile, stretch their hands out their windows, and pass along the peace offering.

In Bama, soldiers, armoured trucks and weapons were common features on the streets. Residents and soldiers lived and worked closely, and it was their version of normal.

Some abandoned filling stations, aged by the conflict, were being used by soldiers to camp their trucks and tanks, while sandbags served as barricades.

The city had seen its fair share of gun battles, armed exchanges and bloodletting, but despite some of the structures looking like relics, there was still noticeable calm about it.

Pupils in uniformed shirts and shorts rode bicycles cheerfully down streets while going home after a long day at school. This was in stark contrast to the attempts to scurry for safety when terrorists invaded here eight years ago.

One thing was certain, Bama was re-experiencing peace. It was not the same city it was in 2014, and definitely not the city Bukar, Abubakar and Murimaina left, but it was not the terror hotbed it used to be.

Despite this, there were a number of unanswered questions. Bukar was unconvinced about why the government closed the formal camps while supporting other informal camps, the Bama IDPs in Dalori wondered why promises made to them were not fulfilled, and there were questions about the government’s adherence to international best practices for treating IDPs.

200,000 IDPs SUFFER AS ZULUM DEFENDS CLOSURE

In January 2022, Babagana Zulum, Borno State Governor, said his government decided to shut down IDP camps due to criminal activities that occur in them.

In his new year message to the state residents, he said he wanted to give dignity to people of the state.

“We closed the IDP camps to clean up the places and give our people dignity as well as purpose,” he said.

“Living in IDP camp is not what we are used to or what we like as a people. Therefore, we believe that a safe life of dignity is a right for all citizens of Borno and indeed Nigeria.

“The IDP camps were becoming a slum where all kinds of vices were happening, including prostitution, drugs and thuggery in some cases. No responsible leadership will allow people to live an undignified life under its watch.”

After camps shut down in August, a report found that the government’s actions violated the rights of the displaced, who did not have alternative housing, feeding and livelihood.

No fewer than 200,000 persons were left in worse conditions than they were when they first sought shelter in the camps.

Some of the displaced who visited Bama after the camp closure revealed that the government had not rebuilt their houses, and they had nowhere to live. Bukar earlier told FIJ that the site where his house used to be is now “empty”.

“Many children have resorted to begging on the streets to survive despite the dangers of road accidents, kidnapping, trafficking, and sexual violence,” this report noted.

INFORMAL CAMPS DOING THEIR BITS, BUT OVERWHELMED BY CHALLENGES

At Madinatu camp, Maiduguri, one of the informal IDP camp owned and run by private individuals and organisations, the presence of a government official was in contrast to Zulum’s position on restoring dignity to people of the state.

The government was fine with camps as long as it was not the one running it or providing for the needs of the displaced persons.

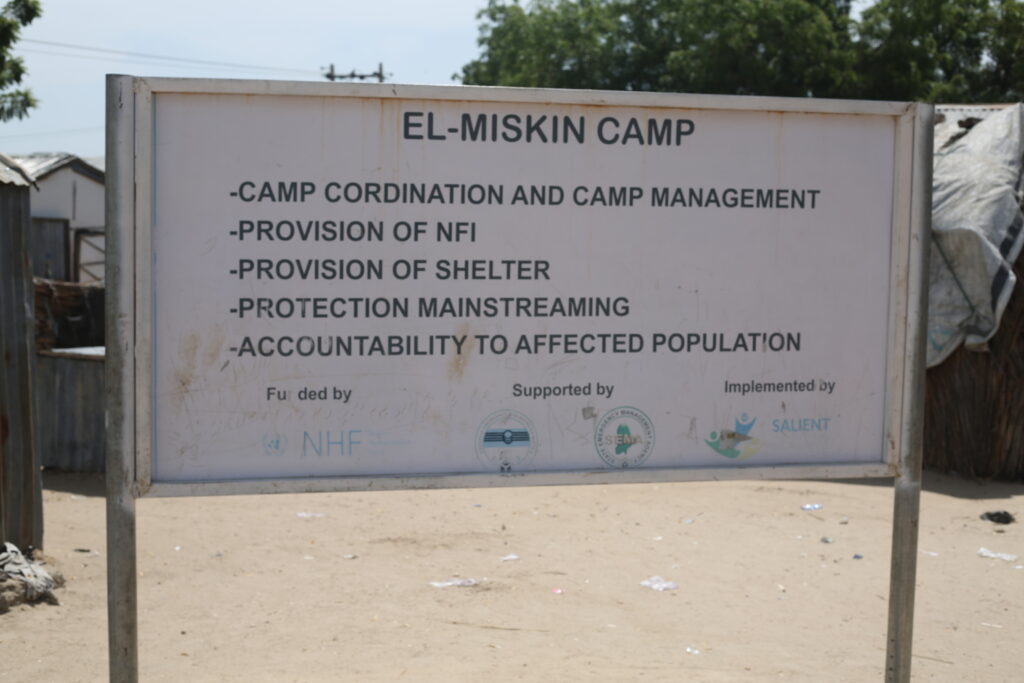

At El-miskin camp, Mohammed Garba, an administrator, told FIJ that the government was present in the camp for administration. He said the government was not providing funding for the camp, but was generally overseeing operations.

He explained how a generous land owner offered an expanse of his land for use by displaced persons sometime in 2014 when the crisis thickened.

He said when the compound’s occupants grew in number, foreign aid groups took notice and began providing support in form of shelter, food and others.

“The plan is, before the government moves people back to their original locations, a thorough assessment would be carried out in the camp with the help of the government agency, which is SEMA,” Garba explained to FIJ.

“A thorough assessment would be carried out to find the number of people from a particular local government or particular village. Then the second step is trying to see if they’ve been able to construct houses, hospitals, schools and security is being provided in that location. Then evacuate them and return them to their previous place of residence.

“It is the government’s responsibility to rebuild these communities. When the government says it is time for people in this camp to go back, then they must have built houses for them. They can’t just return. The agreement is that before they can move people back, there are some basic things that should be in place, like shelter, good drinking water, health facilities, schools, electricity.”

According to the International Humanitarian Law (IHL), “states have a duty to provide displaced people with lasting return, resettlement and reintegration solutions, and displaced people must be involved in planning and managing measures that concern them”.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), in Principle 7, Section 2 of its guiding principles on internal displacement, states: “The authorities undertaking such displacement shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to the displaced persons, that such displacements are effected in satisfactory conditions of safety, nutrition, health and hygiene, and that members of the same family are not separated.”

On resettlement and reintegration, its Section 5 details international best practises ignored by the Zulum administration. This section reads:

Principle 28

1. Competent authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to establish conditions, as well as provide the means, which allow internally displaced persons to return voluntarily, in safety and with dignity, to their homes or places of habitual residence, or to resettle voluntarily in another part of the country. Such authorities shall endeavour to facilitate the reintegration of returned or resettled internally displaced persons.

2. Special efforts should be made to ensure the full participation of internally displaced persons in the planning and management of their return or resettlement and reintegration.

Principle 29

1. Internally displaced persons who have returned to their homes or places of habitual residence or who have resettled in another part of the country shall not be discriminated against as a result of their having been displaced. They shall have the right to participate fully and equally in public affairs at all levels and have equal access to public services.

2. Competent authorities have the duty and responsibility to assist returned and/or resettled internally displaced persons to recover, to the extent possible, their property and possessions which they left behind or were dispossessed of upon their displacement. When recovery of such property and possessions is not possible, competent authorities shall provide or assist these persons in obtaining appropriate compensation or another form of just reparation.

Principle 30

All authorities concerned shall grant and facilitate for international humanitarian organizations and other appropriate actors, in the exercise of their respective mandates, rapid and unimpeded access to internally displaced persons to assist in their return or resettlement and reintegration.

IDPS’ SELF-BUILT TRADITIONAL TENTS

Garba also told FIJ that in the El-miskin camp, there were over 1,500 households, and almost 8,000 individuals, with every childless couple receiving a stipend of N15,000 monthly, and households with over 10 members N30,000 to N38,000.

An average childless couple received N7,500 per head by that math, while a family of 10 was getting N3,000 to N3,800 per head.

Garba explained that there had been cases of residents of Maiduguri infiltrating the camps to get food and other benefits, and perpetrate crimes.

He said vigilantes had on several occasions nabbed rapists and thieves, but it was safer for the displaced persons in the camp than if they were left to wander the city directionless.

Hajiya Ya Bawa Kolo, Director-General of SEMA in Borno, did not grant FIJ audience. He also did not repsond to an email to the agency.

This report was produced with support from the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA)

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.